Design Education, Part I: Peter Biľak

Well-known international design instructors answer our poll about job opportunities for design graduates, the differences between academic theory and real-world practice, specialisation vs general education, and their own motivations to teach design. (This is the full version of the poll published in TYPO 43.)

Design Education

Educators shaping the direction of design in a period of fundamental change in the publishing industry

Palo Bálik, Marcel Benčík, Tomasz Bierkowski, Peter Biľak, Min Choi, Patrick Doan, Richard Doubleday, Will Hill, Gerry Leonidas, Loîc Le Gall, Kristjan Mändmaa, Jacek Mrowczyk, Titus Nemeth, Ivar Sakk, Ewa Satalecka, Silvia Sfligiotti, Martin Tiefenthaler, Gerard Unger

The direction graphic design will take in the coming decades depends a lot on the educational institutions that teach the subject, and especially on the people there who teach design. As the editors of TYPO, we constantly encounter this issue as most of us—and the majority of our contributors—are regular or featured lecturers or workshop leaders at various schools around the world. We have decided to bring the education debate from our editorial meetings to the pages of our magazine so as to foster discussion about education today, and hence the future of the industry.

Peter Biľak, KABK, Netherlands

What motivated you to decide to teach design and/or typography?

It is a good addition to my daily design work. Since I mainly work by myself, having weekly lessons combines well with my schedule. It also means constant learning – something I probably would not force myself to do if I didn’t teach.

Can you estimate about how many graphic designers your country graduates each year? Are there job opportunities in their field?

I don’t have precise numbers, but my rough estimate would be 500–800 graduates. Most of them find job opportunities in their selected fields.

Does your school find that there is a certain gap between “the real world” and what students learn at school? If so, how do you deal with this issue?

I think this happens everywhere – it is in fact desired that schools differ from the ‘real world’ experience. Schools should be safe havens where one can experiment with little risk involved and not feel constrained by future limitations. Of course, students are exposed to professional life too – they go on internships and undertake small projects as well.

Should schools provide a universal education in graphic design, or is it important these days to specialise in specific areas and tasks?

Schools have different traditions and it is not bad to build on those foundations. It would probably be hard to transfer certain educational methodologies to places with different conditions and traditions.

Do you think it is a good idea for students to work on actual commercial contracts while they are still in school? Should the school and the instructors at the school support this?

As mentioned earlier, it is desirable that there be a clear distinction between school and professional practice. It is not wrong to have professional experience in final years of the curriculum, but it is not healthy to simulate a commercial environment within schools.

Many (MA) students return back to school after working professionally – so they explicitly seek a place which is different than their previous daily practice.

Peter Biľak, Eroica, dance performance scene design for the Göteborg Opera, 2010

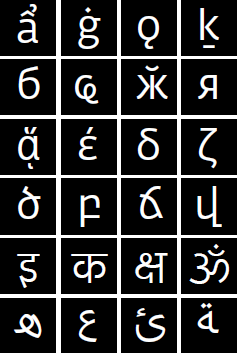

Peter Biľak, Fedra Sans World, font for Decode Unicode book, 2001–2011

Add Comment

Author’s latest articles

- By Design conference in Bratislava 11. 5. 2014

- Live from Typo Berlin 15. 5. 2013

- Download Typo for your iPad! 4. 12. 2012

- Design From Best 2012 18. 6. 2012

- Slanted issue # 17 – Cartoon / Comic 30. 4. 2012

editors

editors

Comments (0)